FROM GOLDSTEIN'S BOOK

GUIDE FOR COLLECTORS

Goldstein arrived in Scotland in 1959 September, and first worked for three weeks ‘under the direction of Hamish Henderson at the School of Scottish Studies’ in the University of Edinburgh. Henderson then took KG and his family north to Buchan, ‘traditionally the most vital folklore area in all of Lowland Scotland’.

‘In Buchan two days, reporters from three different local and national newspapers descended on my newfound residence to interview me and my family.’

In the first interview he did not make any direct appeals [October 1959] but got seven letters and ten phone calls. Two weeks later the same reporters called again. This time Goldstein asked for songs, stories, leads to informants. Got thirty letters and phone calls, led to materials and excellent informants. North eastern Scotland offers no difficulties whatever over the educational affiliations of collectors. The Scots countryman admires education and learning.’

Where religion has driven secular singing out, KG paid as much attention to other members of the household as to the singer. One husband said, ‘Ye dee hae a wye wi the wifie. She’s aye fair scunnert fen I sing tae masel or ma freends, but she disna mind a weet fen I sing tae yersel.’

KG went to schools, and got 142 booklets of collecteana from ages 9 to 14. Eleven children from these provided ‘a fine sampling of the rhymes, games, riddles, tongue=twisters, taunts, and other lore in the repertoire of that community’s school children.’ Also led him to interview 23 adults, five of whom were excellent informants. The landlady of the family’s Strichen home was extremely superstitious and shared a cross-section of the many beliefs of the community.’

Lucy Stewart gave him tales, rhymes, etc but not songs and ballads for the first two months. On one occasion he gave a lecture I the local library o traditional singing, playing some of his local tape recordings, leading to finding new informants. One informant could only recall fragments of his songs in an artificial context. KG took his equipment to the singer’s shoe repair shop and while repairing KG’s chose ‘he performed thirty ballad without pause, hesitation or memory loss.

Goldstein was recording a group of girls of 12 and 13 [possibly gathered by Francis Stewart]. They started whispering – perhaps feeling some rhymes were too rude? KG showed them how to operate the tape recorder and left the room. After an hour there was a reel of ‘their own peer-group erotica and esoterica’. [I have not yet been able to identify this reel, which was not I think copied to the SSS.]

Goldstein had come to Scotland because he had heard 1951 recordings by US collector Alan Lomax. Lomax had been guided to Aberdeenshire singers by Hamish Henderson, who saw how Lomax worked and recorded. Henderson went on to be Scotland's best-known collector, recording thousands of hours from hundreds of informants, and inspiring the work of many others.

Elizabeth Stewart wrote 'A stranger cam tae the prefab we lived in, jist turned up at the door o 27 Gaval Street [in 1954]. He said his name wis Hamish Henderson an that he’d jist come fae the Huntly Stewarts. Geordie, my mither’s brither, had sent him doon efter tellin him the the Stewarts o Fetterangus were weel-kent for their music an songs an that my aunt Lucy and my mam had the songs an ballads that he wis lookin for.'

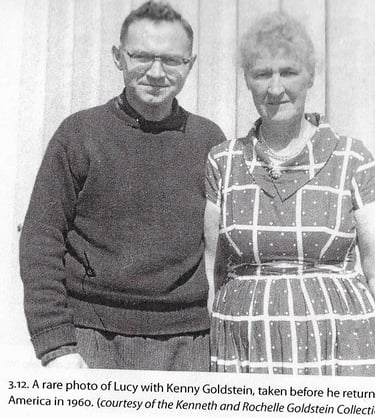

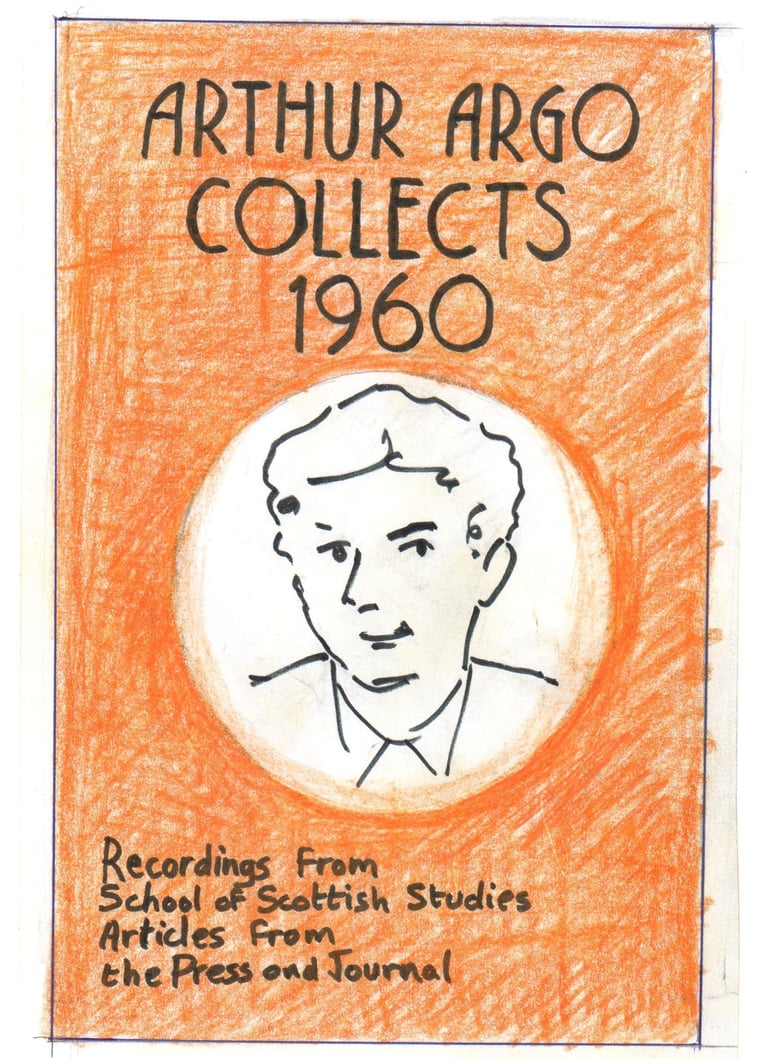

On his return to the US Ken Goldstein wrote a 'Guide for Collectors' based on his Buchan work, including narrative examples - see below left. In Buchan he was interviewed by Arthur Argo, then a cub reporter for the Aberdeen Press & Journal. Argo not only wrote a series of articles, but became a collector and important activist in the 1960s Scottish Folk Revival - see below right.

FROM ARTHUR ARGO'S SERIES OF 1960 ARTICLES FOR THE P&J

Pilgrims Of The Corn Kist Monday, 30th May 1960

The old songs that came to life with the rhythmical dirding of tackety boots against the corn kists of the North-east are, thanks to TV, known now to millions. Folk song is booming – but the full richness of our folk heritage is known only to the experts who, following in the footsteps of Gavin Greig, are combing the countryside for hidden treasure ... In the series which starts today we lift the curtain on that quest

Bennachie Rock Is Born In A Prefab

It seemed completely incongruous to start off a search for classics of the cornkist and for barely surviving remnants of folklore in the living-room of a prefab. How wrong can one be? There, in that prefab, we found a treasure-house of lore, legend and song dating back to the seventeenth century. This visit, made with Kenneth S. Goldstein, an American Fulbright scholar and folklorist from Pennsylvania, was one of the highlights of a fascinating week-long safari I made with him last month during his quest for folk material in Buchan.

Goldstein is visiting Buchan to get material for his doctorate thesis at Pennsylvania University, and already he has collected masses although he arrived here only seven months ago. What sort of man is this Goldstein who, in his short spell here, has already become well known throughout the area and beyond? As with all folklorists, his main qualification is an over-riding interest in his subject. Strangely, although his sights are focused principally on folk music, he never sang until he arrived in Buchan. Now, his slight shyness in that direction has been broken down. In no other direction is he shy, although he has none of the brashness of what is popularly imagined to be the typical American. Instead, he speaks with an authority and confidence born of sound knowledge of his subject.

Perpetual motion is the phrase which springs to mind when referring to him. He rises early, goes to bed late, and in between works unceasingly to add still further to his knowledge of his subject – which takes some doing when you are Kenneth Goldstein, already one of America’s leading folklore theorists. Physically, he is around average height and build. In his own intellectual field, however, he is a giant. Listen to him on Buchan: ‘Within ten miles of one of the most modern scientific installations in all Scotland (at Tyrie) can be heard the bearers of some of the most ancient traditions in the country…

For centuries, Buchan has been one of the most folkloristically rich communities in the entire English-speaking world…. It is a relatively bleak land, mostly devoid of trees and picturesque scenery…. but its inhabitants are as rich in spirit and the ‘guid’ way of life as any people can be ….’

Remarks like these stimulated my interest when I first met him, but the one which persuaded me to devote my holiday to this folk-song safari was: ‘More than fifty years ago, the greatest of all Scottish folk-song collectors, Gavin Greig, found a wealth of traditional material in Buchan….’

GAVIN GREIG WAS MY GREAT-GRANDFATHER.

The idea of playing even a small part in a re-survey of the same field fifty years after his major work had been accomplished in Buchan, was more than I could resist. Greig, therefore, was our common interest – our jumping-off point.

We met at Rosebank, Strichen, Goldstein’s temporary home. Our first stop was Gaval Street, Fetterangus, and the prefab home of the Stewart family. Inside, I was introduced to Goldstein’s greatest ‘discovery’ in Buchan – fifty-eight-year-old Lucy Stewart. Actually, Lucy was ‘discovered’ by Hamish Henderson, of the School of Scottish Studies at Edinburgh University. But Henderson, making a comparatively rapid survey of the area, had neither the time nor the facilities to plumb the full depths of Lucy’s talents. Intuitively, however, he realized that she had great folk traditions behind her and had great potential as a source of material. It was he who guided Goldstein to the Stewarts.

The wisdom of Henderson’s advice has been conclusively proved. From all the branches of this one family, the American has recorded close on 200 songs, hundreds of traditional stories, legends, riddles, rhymes and miscellaneous folklore material by the score, which will be immensely valuable to him in his research and to the School of Scottish Studies.

Goldstein has, in fact, chosen the Stewart family as the subject of one of his projects, and from a complete study of their traditions, customs, habits, songs, stories and superstitions he will draw sociological, psychological and anthropological conclusions.

Sitting in the prefab, it seemed impossible that any blend between the old and the new, the long-gone past and the present could ever be satisfactorily achieved in the face of such obvious modernity. But within a few minutes of entering the home, I heard Lucy sing, in magnificent traditional style, a beautiful seventeenth-century ballad; join lustily in a chorus of ‘The Barnyards o’ Delgaty,’ and then join with her young nieces in a rock ‘n roll version of ‘The Hill o’ Bennachie,’ a song they learned traditionally from their aunt before translating it to the modern idiom. In its new guise, they call it ‘Bennachie Rock.’ Set to a heavy driving beat, brought out by Elizabeth’s pianistic wizardry and her mother’s virtuosity on the accordion, Jane sang out Lucy’s traditional words in her quaint high-pitched style. Their song may soon have a wider public for the Stewarts have sent a tape-recording of it to a record company which plans to issue it. What did Lucy think of this ‘jazzing-up’ of the classics of tradition? Did she agree with the purists in condemnation of this style? Her answer was to join in the chorus with the girls!

In his months in Buchan, Goldstein has uncovered many songs which have come down in their traditional style from the pre-Burns days, although the poet re-wrote and issued more ‘literary’ versions. The obvious deduction is that the folk preferred the ‘folk’ variants.

Coincidence

When I first played over a tape made by Mrs Margaret Adams from Darnabo, Fyvie, to Kenneth Goldstein, he thought I was playing a trick on him. To find out, he went to his recorder and played back a tape made by Mrs Jean Matthew, Auchtydore, Longside. There was the same repertoire, sung in a similar sequence, the textual and melodic resemblance was strong, and, when allowances were made for the differing ages of the singers, the styles of presentation were almost identical. But nowhere could we find a link between the two. At no time, apparently, had their paths crossed, nor did they get their songs from the same source. They did not even come from the same area.

Last month Kenneth Goldstein and I were given a fragmentary version of a song from Mrs Jean Stewart, of Banchory. When we had taped ‘Sir James the Rose’ and were satisfied that she knew no more of it, she mentioned out of the blue, that she had a book which contained more of the words.

This she produced and it turned out to be the first volume of ‘Greig's Folk-Song of the North-East’, a book I have eagerly sought for years. Incidentally, I still do not have a copy. Would another appeal for assistance do any good?

During that trip with Goldstein, we discussed the folk songs which are still in common currency in the North-east and a surprising fact emerged. From his experiences, he has found that the songs with ‘a thread of blue’ as they are known colloquially are always the most generally popular